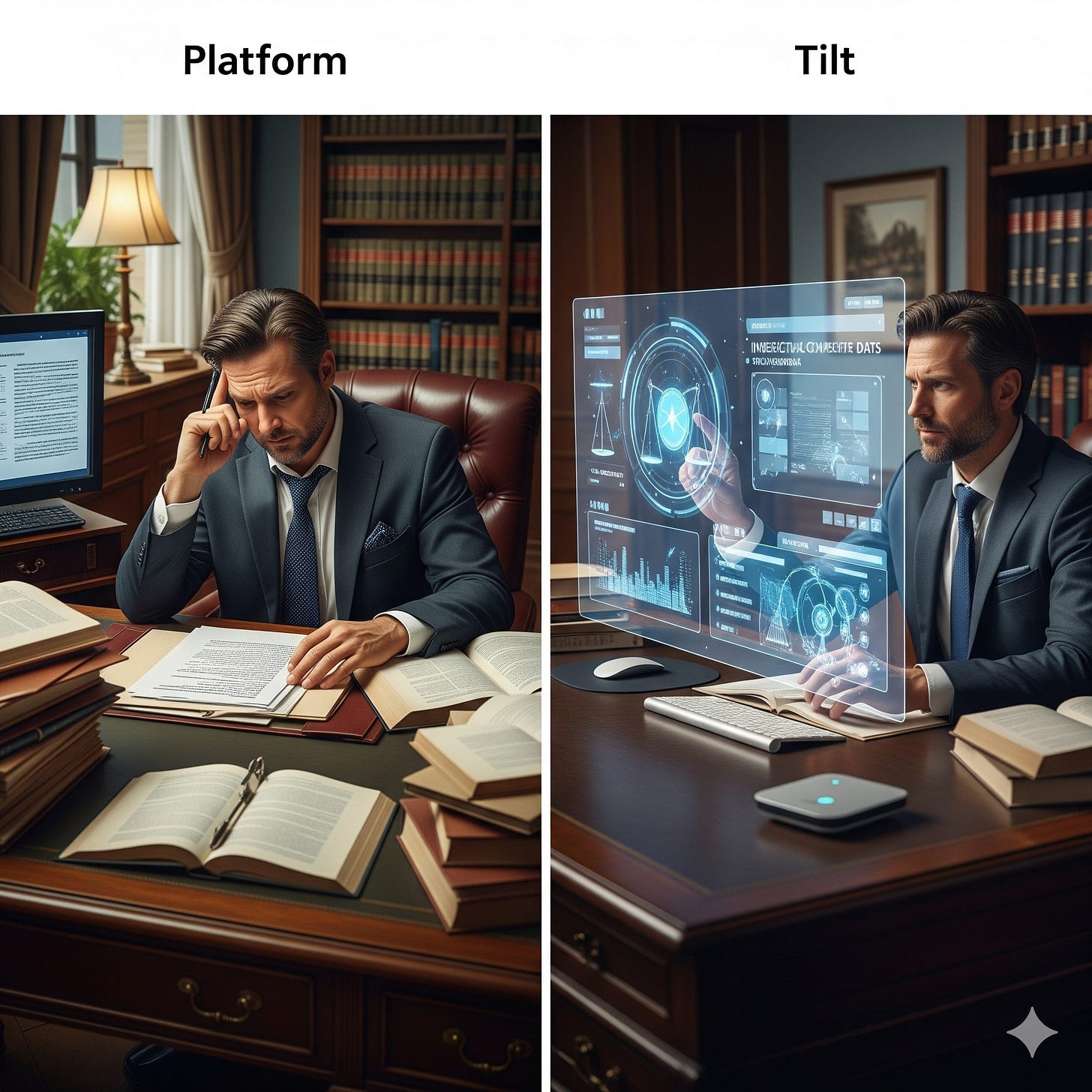

The Difference Between Playing With AI and Mastering It

Or why most lawyers are typing the legal equivalent of "write me a good contract"

I've been watching lawyers and non-lawyers interact with AI about the law for the past few years, and I think we should help everyone level up.

Instead of typing "review this agreement" into ChatGPT, pasting in 30 pages of text, and then looking confused when the response is generic mush, rife with hallucinations, you should be doing more.

It’s cargo cult AI usage at best: going through the motions without understanding the mechanics.

So here's a series of A/B tested prompts designed to show you exactly what makes the difference between amateur hour and actual capability.

Each pair contrasts a prompt that'll get you nowhere (B) with one that demonstrates relative mastery (A). You’re more than welcome to try them yourself and see whether the response is materially different!

Like learning to cross-examine. Once you understand leading questions, you don't need a word-by-word script.

The Power of Specificity & Context

Let's start with the most basic mistake I see everywhere.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Act as a UK-based intellectual property solicitor. I am a founder of a new SaaS startup. Explain the difference between a UK registered trademark (®) and an unregistered trademark (™) in the context of software brand names. Focus on the concepts of 'enforceability' and 'passing off'. Keep the explanation under 300 words.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

What's a trademark?

See the difference? The model isn't psychic – it needs context, jurisdiction, perspective, and constraints.

This aligns with what I call the CLEAR principles: Concise (under 300 words), Logical (structured request), Explicit (UK law, software context), Adaptive (can be modified for other IP types), and Reflective (focuses on key legal concepts).

The COSTAR Framework in Action

Here's where we get more sophisticated. COSTAR – Context, Objective, Style, Tone, Audience, Response format from Singapore’s GovTech.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

<Context> I am a paralegal at a corporate law firm preparing a memo for a senior partner. We are representing a client acquiring a small tech company in Delaware. <Objective> Provide a checklist of key items to look for during the due diligence process regarding the target company's intellectual property assets. <Style> Use a clear, hierarchical bullet-point format. Use bold headings for categories like 'Patents', 'Trademarks', 'Copyrights (Software)', and 'Trade Secrets'. <Tone> Formal, professional, and precise. <Audience> A senior corporate lawyer with 20+ years of M&A experience who values brevity and accuracy. <Response> The response should be a checklist, not a long-form essay.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Tell me about M&A due diligence.

Prompt B is what I see partners asking their juniors. It's lazy. Prompt A? You're not just asking for information. You're architecting exactly and explicitly what you need.

Show, Don't Just Tell

One-shot example prompting is like showing a junior exactly how you want a document formatted instead of vaguely waving your hands and saying "make it professional."

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Draft a 'force majeure' clause for a commercial supply agreement governed by the laws of England and Wales. The clause should be robust and list specific, non-exhaustive examples. Here is an example of the kind of clear, modern drafting style I'm looking for (using a different clause): "**11.1 Confidentiality.** Each party undertakes that it shall not at any time disclose to any person any confidential information concerning the business, affairs, customers, clients or suppliers of the other party, except as permitted by clause 11.2." Now, based on that style, draft the force majeure clause.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Write a force majeure clause.

The example in Prompt A isn't just decoration. We learn by example; models emulate examples. This is the difference between getting something you can use and something you have to completely rewrite.

Structured Output That Actually Works

Want to know why most AI-generated legal analysis is useless? Because lawyers ask for "thoughts" instead of structure.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Create a comparative analysis of the discovery process in US federal courts versus the disclosure process in the UK's civil courts. Present the information in a Markdown table with the following columns: | `<Process Stage>` | `<USA (Federal Rules of Civil Procedure)>` | `<UK (Civil Procedure Rules)>` | `<Key Philosophical Difference>` | |---|---|---|---| Include at least four stages, such as 'Initial Disclosures', 'Scope', 'Document Production', and 'Depositions/Witness Statements'.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Compare US discovery and UK disclosure.

Structure > systematisation > systematic analysis. You’re not writing exam questions for the model. It’s a colourful example from your own history, but it doesn’t mean it’s the right thing for models.

The Power of Conversation

Good lawyering is iterative. So is good prompting. Prompt chaining – building on previous outputs – mirrors how we actually develop legal arguments.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Prompt 1:

Identify the top 5 most contentious issues typically negotiated in a shareholder agreement for a tech startup with multiple co-founders. List them as a numbered list.

Prompt 2 (after receiving the list):

Excellent, thank you. For item #2 on your list ('Vesting of Shares'), please draft a sample clause from a pro-company perspective that includes a 4-year vesting period with a 1-year 'cliff'.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Prompt 1:

What are some issues in a shareholder agreement?

Prompt 2:

Draft a vesting clause.

See how Prompt B loses all context between interactions? That's like asking a junior to draft a clause without telling them which deal it's for. Prompt A maintains the conversation thread, building complexity naturally.

Tell It What NOT to Do

Sometimes the most powerful instruction is a prohibition - covered in any law 101.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Explain the legal concept of 'frustration of contract' under English law. Provide one key case example. **Do not** mention or use examples from US law, particularly the doctrine of 'impossibility' or 'impracticability'.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Explain frustration of contract.

Prompt B will give you a global mishmash. Prompt A keeps you in the right jurisdiction.

Pattern Recognition Through Examples

For complex analytical tasks, multi-shot prompting – providing multiple examples – teaches the model to recognise patterns. It's like training a junior through precedents.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

You are a legal analyst reviewing a closing argument for logical fallacies. I will provide you with examples of the task, and then a new statement to analyze. <Example 1> Statement: "My opponent argues that the contract is ambiguous, but he failed to file his motion on time last month, so his argument should be disregarded." Analysis: This is an **Ad Hominem** fallacy. It attacks the opposing counsel's procedural conduct rather than the merits of the contract ambiguity argument. <Example 2> Statement: "If we allow this merger, it will inevitably lead to a complete monopolization of the entire industry." Analysis: This is a **Slippery Slope** fallacy. It asserts that a relatively small first step will lead to a chain of related events culminating in some significant effect, without sufficient evidence. <Your Task> Analyze the following statement using the same format: Statement: "The expert witness must be wrong about the cause of the structural failure; after all, he admitted he has only been a licensed engineer for five years."

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Is there a logical fallacy in this sentence: "The expert witness must be wrong about the cause of the structural failure; after all, he admitted he has only been a licensed engineer for five years."?

The examples in Prompt A aren't just helpful. You're teaching the model your analytical framework in real-time.

The Implicit Framework

Circling back. Sometimes the best prompting doesn't need to signpost the framework that you’re using. It just embodies good principles naturally.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

You are a junior associate. Review the following 'Limitation of Liability' clause from the perspective of the **customer**. <Clause> "The Service Provider's total aggregate liability arising under this Agreement shall not exceed the total fees paid by the Customer in the preceding six (6) months." Identify two primary risks for the customer in this clause and suggest a specific revision to mitigate one of those risks. Present your answer with the headings: `Identified Risks` and `Proposed Revision`.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

What do you think of this limitation of liability clause?

Prompt A doesn't name-drop frameworks, but it's Concise (no fluff), Logical (structured task), Explicit (clear perspective), Adaptive (works for any clause), and Reflective (analytical output).

Chain of Thought for Complex Analysis

This is where we separate the intermediates from the amateurs. Chain of thought prompting makes the model show its work – just like you'd demand from a junior.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Analyse whether an email exchange can form a legally binding contract under the laws of New York. First, outline the essential elements required for contract formation in New York (offer, acceptance, consideration, mutual assent, intent to be bound). Second, discuss how these elements can be manifested through digital correspondence like email. Finally, conclude with a summary of the likelihood and potential pitfalls.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Can an email be a contract in New York?

Many of the ‘thinking’ models now do this. Different model providers have different ways of accessing these models.

Bringing It All Together

This final example combines everything – persona, context, structure, examples, and specific outputs.

Prompt A (Good) 👍

Act as General Counsel for a financial services firm regulated by the FCA in the UK. Draft a concise, firm, and professional-sounding paragraph for an internal memo to the trading desk. The purpose is to remind them of the firm's strict prohibition against using non-approved communication channels (like WhatsApp) for business-related discussions, citing regulatory risk under MiFID II. For tone, consider this example: "**Reminder: Personal Trading Policy.** All staff are reminded that personal trading accounts must be declared to Compliance in accordance with the Firm's approved policy. Failure to do so constitutes a serious breach." Now, draft the paragraph regarding <communication_channels>.

Prompt B (Bad) 👎

Write a memo telling traders not to use WhatsApp.

This is the difference between someone who understands AI as a tool, and someone who's just treating legal AI like Internet Relay Chat.

The Real Test

Here's your homework – because mastery requires practice. Take these prompts and run them yourself. See the difference in outputs. Then take a real task from your practice and apply these principles.

That's four different prompts, each building on the last. That's the difference between cargo cult AI usage and actual proficiency.

The legal profession can keep playing AI games – the LinkedIn posts, the vague announcements, the expensive subscriptions to tools we don't fully understand. Or we can develop real capability.

Because here's what's coming: clients who've learned to do this themselves. Who only need you for the final sign-off. Who've embedded these capabilities into their workflows so deeply they don't need to wait for you or pay your hourly rate for first drafts.

The software engineering world is already there with agent-assisted coding. What makes you think law is immune?

We're still asking AI to behave like associates, to magically understand our half-formed thoughts. But that's not how these tools work. They're not junior lawyers. They're something else entirely – powerful, precise instruments that reward specificity and punish laziness.

Oh, and I used AI to help me draft these prompts!